The Hidden Origins of Lisp: The Place of Lisp in the 21st Century

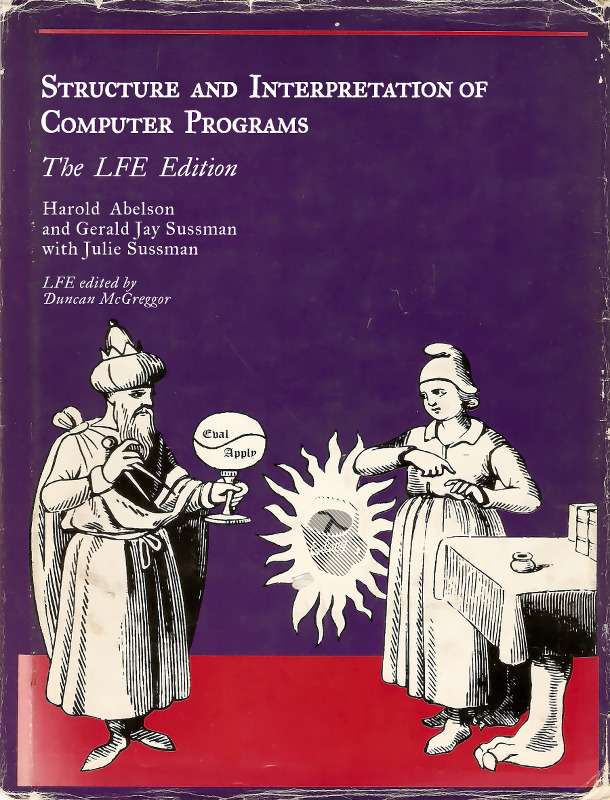

With this post we reach the end of the blog series highlighting the new preface for the LFE

edition of Structure and Interpretation of Computer Programs.

(book,

source) Below we ponder the question of Lisp's

pertinence to a field that has changed greatly since its beginnings in the

1940s and 1950s, a field that is almost defined by how much it changes. What

used to be unique characteristics of Lisp have have steadily – over the course

of more than 50 years – been integrated into old and new programming languages

alike. So, in particular, we ask weather Lisp still has something unique and

compelling to offer current and future generations of computer programmers.

With this post we reach the end of the blog series highlighting the new preface for the LFE

edition of Structure and Interpretation of Computer Programs.

(book,

source) Below we ponder the question of Lisp's

pertinence to a field that has changed greatly since its beginnings in the

1940s and 1950s, a field that is almost defined by how much it changes. What

used to be unique characteristics of Lisp have have steadily – over the course

of more than 50 years – been integrated into old and new programming languages

alike. So, in particular, we ask weather Lisp still has something unique and

compelling to offer current and future generations of computer programmers.

The list of posts for this series are as follows:

- Introduction

- Giuseppe Peano

- Bertrand Russell

- Alonzo Church

- John McCarthy

- The Place of Lisp in the 21st Century

If you find any issues or have questions, concerns, etc., you may provide feedback about the preface in the dedicated ticket created for tracking just such things.

The Place of Lisp in the 21st Century

The ups-and-downs of Lisp since its inception in 1958 have been covered in various media since the late 1970s. 1 While Lisp continues to have its supporters and detractors, one thing is abundantly clear: many of the characteristics initially touted as making Lisp unique and powerful are now shared by a vast majority of modern programming languages. By some, this is considered the greatest triumph of Lisp, a source of inspiration for much of modern computing. The inevitable question is then asked: what use is Lisp, more than 50 years after its creation, when the world of computing – both research and industry – are so vastly different from what they were in Lisp's early days?

The first answer usually given is one that requires very little thought: macros. There are numerous books written on this topic 2 and we will not cover it further in this preface, but accept as a given that the support of Lisp-style macros in any programming language is a powerful tool.

Once we get past the obvious answer, subtler ones come to the fore. For instance, the simplicity of the syntax and similarity to parenthetically grouped algebra expressions make for an easy programming introduction to students of a middle school age. This simplicity is also something offering great insights to experienced programmers. Alan Kay's famous quote of Lisp being the software equivalent of Maxwell's famous partial differential equations for classical electrodynamics3 derives its inspiration from this simplicity: one can fit the essence of the language in one's head or on a single sheet of paper.4

The education point is important: if we cannot teach the basics of a science or a branch of mathematics – regardless of how profound it may be – it has ceased to become a science and should at that point be considered a superstition or cargo cult, with its practitioners engaged in a great deal of activity (or even lucrative commerce) but having no understanding of the principles which form the basis of their work. However, to be a compelling focus of study, the value of Lisp in the 21st century most hold more than simply the promise of clarity and the means by which one might create domain-specific languages. To be genuinely pertinent, it much reach beyond the past and the present to provide keys to undiscovered doors for each new generation of intrepid programmers.

And here the answer arrives, not as some astounding epiphany, but again in humble simplicity: Lisp's fun and its beauty rest not only in its syntactic elegance but in its power of expression. This is specifically important for the adventurer: if you want to create something new, explore some new programmatic territory, you need tools at your fingertips which will allow you to do so flexibly and quickly, with as little overhead as possible. Otherwise the moment of inspiration can be to quickly lost, the creative process swallowed in a mire too heavy with infrastructure and process.

By putting the power of Lisps into the hands of each generation's aspiring programmers, we are ensuring that they have what is necessary to accomplish feats which might seem miraculous to us should we see them now – as genuinely new ideas often appear (when appreciated). A world that sees the rise of quantum computing or the molecular programming of nano-scale machines or as yet undreampt technological capabilities, will need programmers who have the ability to iterate quickly and try out new ideas, easily able to see that which should be abandoned and that which should be taken up.

This is especially important for the survival of free software: as long as our societies are able to produce languages, software, and systems which individuals or small groups may attain understanding and mastery over, software freedom will prevail. Systems that are so complex as to require an industry to manage them are no longer within the domain of motivated and curious individuals, but rather that of organizations with sufficient capital to maintain the necessary infrastructure.

Thus, as we point our technological society towards its future with each action we take, as individuals and as a group, we have a responsibility to maintain the tools which will ensure the freedom of future generations, the basic freedom of the tool-maker, the hacker, the artist, and the poet. Lisp is not the only answer to this particular need, but it has shown its strengths in this regard over the past 50 years. If the last 10 years of re-discovery and innovation in the world of programming is any indication, Lisp is alive and well and will likely be with us for a long time to come.

And there will be even more fun to be had by all.

-

For a large collection of documents on this topic, be sure to visit the Computer History Museum's site. The documents most often referenced for the history of Lisp include John McCarthy's 1978 ACM paper History of Lisp, Herbert Stoyan's 1979 document Lisp History, Guy Steele and Richard Gabriel's 1993 HOPL II paper The Evolution of Lisp, and Paul Graham's 2001 paper The Roots of Lisp. Another gem not often referenced is Herbert Stoyan's 1991 article The Influence of the Designer on the Design – J. McCarthy and Lisp which appeared in Artificial Intelligence and Mathematical Theory of Computation: Papers in Honor of John McCarthy. ↩

-

Peter Norvig's Paradigms of Artificial Intelligence Programming and Peter Seibel's Practical Common Lisp both provide an introduction to using macros, while much of Paul Graham's On Lisp and all of Doug Hoyte's Let Over Lambda are dedicated to the use and understanding of macros. ↩

-

See the ACM-hosted interview with Alan Kay. ↩

-

Or, as the case may be, the lower 2/3rds of a single page. ↩